Marylin Katz: 1968 - Chicago

- Dec 20, 2012

- 11 min read

By: Jon Jost

Grant Park, August 1968

Nineteen-sixty-eight. The words slip off the tongue of those of my generation as a talismanic exclamation point, a vortex of nostalgia. Later generations have heard of it, and waxed romantic, and become latter-day hippies, or tattooed urban primitives. The year reverberates through our culture and politics to this day and beyond. It is celebrated by many as a great turning point, either seen positively or negatively, usually depending on one’s political inclinations. Among my friends it is often the locus of a deep sentimentality, the seeming high point of their lives. Among others it is seen a nadir, the opening volley of a deep culture war still being waged, and with Trump in the White House, seemingly finally being won, despite same-sex marriage, and the myriad other “civil rights” victories of the last decades. Retrenchment is back with a vengeance.

A Prelude

Americans, being provincial and self-centered, tend to see the world with blinders. What is seen and known is all about America’s involvement somewhere far away. In 1968 that meant Vietnam, though most knew little of the place, only that we were at war there. The Tet offensive in Vietnam muscled the war front and center in the US. Later on we’d learn a bit about Laos and Cambodia, which, of course, we bombed. Most of the rest of the world was invisible unless something about the US was involved in a way that brought it to the front pages of the newspapers and the nightly news leads.

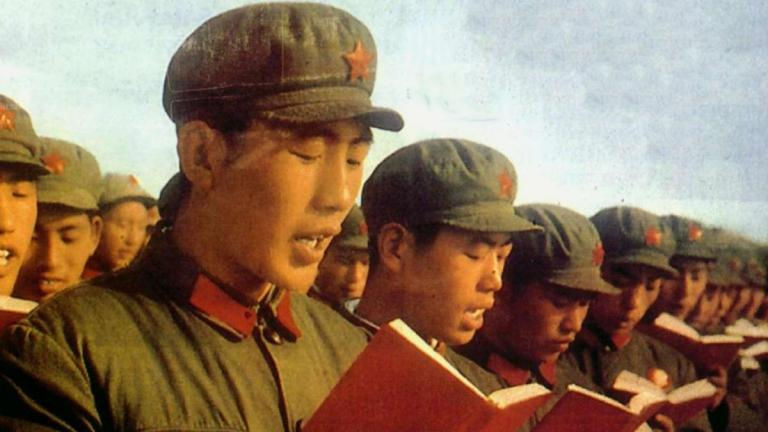

In 1968 the world it seemed was in ferment, from China, deep into the “Cultural Revolution” begun by Mao Tse Tung in 1966, to Japan where student unrest spilled into the streets, from Argentina to France, from Germany to Mexico. The stasis of the post-WW2 era and all its institutional structures were under stress and challenge. Around the world people took to the streets demanding change. In Eastern Europe discontent under the yoke of the Soviet Union burbled just beneath the surface and broke out in the open in Prague. Across the Western world the same strains seemed to spread contagiously from country to country, bringing uprisings in Paris, Rome, Berlin, Poznan, Prague, Buenos Aires and elsewhere. It seemed a great cultural and political uprising had commenced, bringing for many a great sense of both danger and hopefulness. It occurred not simply in the political realm, but culturally – in music, theater, cinema, literature: seemingly a kind of great awakening.

In summer of 1968 I was just 25 years old, a touch more than a year out of Federal Prison, where I’d resided 27 months, having refused to comply with the Selective Service system. On getting out in ’67 I’d immediately jumped into the political fray, figuring I’d earned the right to do so having done time. I worked with the nascent draft resistance movement, and was deployed to talk about the prison experience and to encourage people to refuse induction into the military. Though as the clouds darkened I began to say that maybe it would be a good idea to join the military, perhaps learn how to use weapons and then go AWOL with this newly learned skill. I recall the draft resistance people, mostly pacifists, nudging me off the stage, dumping me as a speaker for their cause. Mine was not the view they wanted said on their behalf. At another time I recall giving a fiery talk at the Chicago Art Institute, when I suggested that perhaps the time for assassins had arrived. I remember a young female student coming forward after I’d spoken and asking if I had a copy of my speech and giving her the one I’d just read.

And I shot my own 16mm films – Traps and Leah, my first sound films.

Frame still from Traps

Linn Ehrlich 1967

In the same period, autumn to winter of 1967, I helped organize and set up the Chicago Filmmakers Coop, along with Kurt Heyl and Peter Kuttner and a few others. The three of us later set up what would turn into the Chicago branch of the left-wing Newsreel group. In early 1968 “The Mobe” was setting up in Chicago. “The Mobe” was short for “National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam” which was a coalition of various anti-war groups, including the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which set out in early 1968 to prepare for organized protests at the Chicago Democrat Convention, primarily focused against the Vietnam war, but as well around civil rights and other leftist matters of interest. They had rented office space, and gave our yet unnamed Newsreel group a room to work in. In turn I became involved in the Mobe, meeting most of its organizers – Tom Hayden, Dave Dellinger, Rennie Davis, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and several others whom I do not recall – Lee Weiner and John Froines. I recall talking with Hayden, telling him of my recent prison experience and having him say to me that he didn’t think he could do 2 year stint in the joint. I recall thinking, “And so why are you one of the leaders?”

Tom Hayden

While there I met Marilyn Katz, of the SDS and involved in the Uptown project, in which activists moved into a neighborhood of poor Appalachians and attempted to organize them. I moved in with Marilyn and lived there, with a Chicago “Red Squad” police car often parked at the porch-steps. In April a demonstration which I consciously did not attend was attacked by police, though Peter was there and made still photos, and there was some film footage. I organized and edited a short film, April 27, out of the material – which turned out to be the only film made by Chicago Newsreel. The police behavior on that date foreshadowed what would happen in August.

"Anecdote 1: Sometime in spring of 68, I went with a group to stage some anti-war guerilla theater on the plaza of the Federal Building in the Loop. My role was as an American soldier, pulling out a plastic machine gun to mow down the Vietnamese civilians, a la My Lai. After the theater was done a cop came to arrest me for having a gun, however obviously fake it was. Since leaving prison I’d had a pathological relationship to cops, leaving me quivering at their sight. Marilyn and a friend of hers, an old time Pinko, Sylvia Kushner, came charging and in effect scared the cop away with legal threats, rescuing me from the arrest."

Marilyn at the barricades

The Mobe’s intention was to get at least ten thousand people to come to Chicago, and have a major visible presence during the Convention, and hopefully to influence the nomination process. Hubert Humphrey, stalwart Minnesota liberal, was tipped to be the Democrat choice, though he’d fully signed on to Johnson’s Vietnam war policies.

Two weeks before the convention began, Kurt and I, having read that the Democrats were having a mini-White House portico built onto the entrance of the Stock Yard Convention site, decided it might be a useful image for the film we, and the recently arrived New York contingent of Newsreel, were making about the convention. So we drove on down to the South Side in his banged up VW Beetle, and parked near the site, and went in the August heat, in shorts and long hair and beards, and set up our tripod and got the shot. Returning to the car, as we arrived 6 or 7 police cars swooped in, surrounding us. Arrested, we were taken to the nearest Precinct office, and interrogated, initially by the local cops; then the Chicago Red Squad. Then the FBI, and finally by the Secret Service. As we escalated up the hierarchy the interest lessened – it appeared two wild haired hippies weren’t exactly the would-be assassins scoping out some upcoming killing ground. We called the Mobe office to inform them and as I recall they got a lawyer on it. I was released, but Kurt spent the night in jail as the papers on his Beetle had some problem.

On getting out I went promptly to the Mobe office to report in full what had happened – the first arrests of the Mobilization. My recollection is none of us made a big deal out of it, though it should properly have been a cue as to what the coming weeks would bring. None of us seem to have picked up on it though.

More Marilyn Chicago 68

As the time of the convention rushed closer, the people at the Mobe were busy and concerned: it was clear that 10,000 people were not headed to Chicago as hoped, and we’d be lucky if 1000 showed up. It appeared the whole plan was headed towards a dramatic failure, a fizzle. In light of the events of the previous 6 months – the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the assassination of Martin Luther King, the riots which came in the wake of that event, including large swathes of the west side of Chicago which went up in flames and resulted in the National Guard being called in, and then the assassination of Robert F Kennedy, along with the massive protests in Paris in May and elsewhere around the globe – it appeared the Mobe’s efforts would look pathetic in contrast.

Anecdote 2: "Marilyn and cohorts went to the Federal Building to paint “CIA” on their unmarked door, having asked me to go to film it. I declined, still very nervous about police. I had been in the building 2 and a half years earlier, in a court room being sentenced to 3 years in prison. Marilyn also sprinkled “guerilla mines” in the form of large nails to flatten cop vehicles, and others liberally sprinkled stink bombs in the Hilton Hotel, HQ for the Democrats at the convention."

A night before the convention was scheduled to begin (Aug 26-29) a small band, perhaps 500 to 1000 or so people who had come to Chicago, along with some locals, commenced a march on the Near North Side, where the Yippies, centered around Abbie Hoffman, had set up a camp in Lincoln Park. Hoffman and the Yippies were having a Festival of Life, juxtaposed to what they said the convention was, a The Festival of Death. The police – nervous and touchy, as Kurt and I had experienced – attacked with billy clubs and tear gas, chasing demonstrators and by-standers down the streets and alleyways and making arrests. This was reported locally at first, on the TV news and papers. The result was an instant swelling of the demonstrators to more in the realm of thousands – many of them young people from Chicago and the suburbs, drawn probably as much for the excitement as for any substantive political reason. In the next days the news went national, and in short order there were the Mobe’s wished for thousands.

Mayor Daley in the convention hall

Inside the convention center Mayor Daley fulminated against the demonstrators and the press, his beloved city shamed before the world. His police attacked national press figures like Dan Rather, Mike Wallace and Edwin Neuman both inside and outside the convention hall, resulting in terrible international press. During Senator Abe Ribicoff’s nomination speech for George McGovern, in which he commented on the action happening outside, Daley was caught on camera yelling, “Fuck you, you Jew son of a bitch.” All in all a far from auspicious commencement for the presidential campaign around the corner.

Had the cops laid low the counter-protest to the convention might well have fizzled, a foot-note in history. Instead, by August 28, as Hubert Humphrey was being nominated – defeating Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern, the crowd had swollen to 10,000, including lime-light seeking luminaries including Norman Mailer, Alan Ginsberg, William Burroughs and all the way from France, Jean Genet. Grant Park resembled a quasi-war zone, surrounded with National Guard troops with rifles at the ready, bayonets, and jeeps and trucks with barbed wire grates, hemming in the demonstrators. The Mobe’s leaders and other addressed a vast chanting crowd picking up Rennie Davis’ comment that “The Whole World Is Watching.” And it was.

"Anecdote 3: Watching at night-time some of the police actions around Grant Park, I thought of going to an auto supply store and buying a handful of emergency flares and driving to the west side and heaving them into lumber yards, a diversionary distraction for the police. Didn’t do it, but I did think it."

I was among those in Grant Park, there with Bolex in hand to shoot, though I recall a strong sense of distaste for the behavior of this mass of people, all taking their cues from the podium, chanting as told, and given the actual mix of people – mostly young, many from the region, I had the nagging suspicion that had someone begun a chant saying “Let’s go to the South Side and kill n…..s” a good part of them might well have done so. Since that time I have always avoided anything with mass crowds.

The other thing I felt while in the park was fear. The part of Grant Park we were in on one side was sliced by railroad tracks, maybe 30 feet down, sided by a vertical concrete wall and fence – no escape. The other side, facing Michigan Avenue, was lined with National Guardsmen, literally fencing in the crowd with portable barbed wire mounted on the fronts of their jeeps and trucks. The Guard was armed with rifles, and in my mind, fresh from my experience in prison, I could imagine the rules of the game being shifted, and those guns being fired. While it did not happen then, only a few years later, in May 1970, at Kent State in Ohio and at Jackson State University, Mississippi, the Guard did open up and fire, killing students.

At the conclusion of the convention the delegates dispersed, having nominated the favored Humphrey who limped off, ham-strung, to campaign and lose to Richard Nixon. And likewise did the folks at the Mobe. They’d done their job, and most assuredly had impacted the nation’s politics, in a manner still being debated among the survivors and participants. Back in the office word came that a farmer out west of the city had seen it all on television, and invited us out to his place for a bit of R&R, a picnic in the quiet of the Illinois prairie. Marilyn and I along with 3 others road out for this welcome break. She and I, and Rennie Davis, were sitting in the back-seat, Rennie with a large visible blood-marked bandage swathed around his head. He’d been clubbed by cops during the convention. As we were driving out of the city, he turned to Marilyn and me, and said, “I guess I don’t need this anymore” and he lifted the bandage off his head like a hat and set it aside.

My soul curdled, and inwardly I thought to myself, “This is my side?”

Foto by Linn Ehrlich, on a visit back to Chicago, 1969

In early September Marilyn and I drove her VW to California where for a while she joined up with Bruce Franklin’s radical group in Stanford and bought a Beretta. I hung around the edges of the The Movement, visiting a tear-gassed Berkeley and slowly edged away from the organized left. Nixon won the election ushering in a continuation of the Vietnam war and a long period of America’s recoil from the 60’s and a drift into conservatism, and finally a terminal corruption and corporatism, culminating in Donald Trump. Marilyn went back to Chicago to continue a life-time of work as a social and political organizer and I retreated into a seven year hiatus in the woods in California, Oregon and Montana. Today Marilyn runs a political consultancy in Chicago, and I carry on as a quiet anarchist.

Of the figures who led the Mobe their life paths were wildly diverse:

Tom Hayden married Jane Fonda (and divorced after 17 years), and became a Democrat assemblyman in California and died in 2016.

Rennie Davis became a follower of Guru Maharaji Ji, and later a venture capitalist and advisor on meditation.

Abbie Hoffman carried on as a social critic and theatrically minded activist, writing books and committing political pranks. Wanted for cocaine dealing he went into hiding for some years, and in 1989 apparently committed suicide by drug over-dose.

David Dellinger, a life-time pacifist born in 1919 carried on in his work and died in 2004.

Jerry Rubin, founder of the Yippie party, and carrying on as a political prankster into the mid-70’s Rubin morphed into a businessman, became a millionaire and advocated for Yuppies. He died in 1994 following an accident while jaywalking in Los Angeles.

John Froines, an anti-war activist and scientist (chemistry) went on to a long academic career, retiring from UCLA in 2011.

Lee Weiner, continues to work for social causes, largely around Jewish issues.

Bobby Seale, somewhat dragooned into the event very late while visiting Chicago on behalf of the Black Panthers, of which he was a founder, was bound and gagged during the trial and then severed from the trial to be tried alone. He carried on with the Black Panthers until its demise and since has carried on in various social actions.

Comments